The neoclassical movement of the early twentieth century saw composers attempt to create a groundbreaking musical language by fusing inspiration taken from classical composition with modern musical practices. Stravinsky was one of the key figures to follow this approach.

He not only adopted many stylistic features from earlier periods of composition into his own music, but also often took melodies and ideas from the works of past composers, ‘re-composing’ them into new pieces. This involved re-imagining these musical references with new stylistic twists, such as unusual rhythmic modifications; distinct harmonic effects, such as unexpected dissonances and surprising modulations; and a range of instrumental effects that would have been unheard of in previous eras. Stravinsky’s first such work was the 1919 ballet Pulcinella in which he adapted various pre-existing themes, all of which at the time were said to be by Pergolesi, but which since have transpired to be from a variety of classical

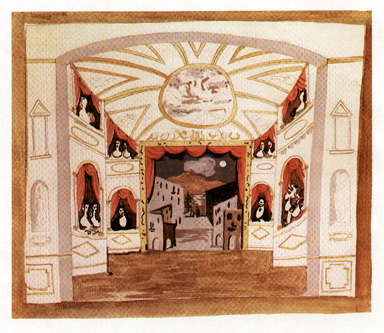

He not only adopted many stylistic features from earlier periods of composition into his own music, but also often took melodies and ideas from the works of past composers, ‘re-composing’ them into new pieces. This involved re-imagining these musical references with new stylistic twists, such as unusual rhythmic modifications; distinct harmonic effects, such as unexpected dissonances and surprising modulations; and a range of instrumental effects that would have been unheard of in previous eras. Stravinsky’s first such work was the 1919 ballet Pulcinella in which he adapted various pre-existing themes, all of which at the time were said to be by Pergolesi, but which since have transpired to be from a variety of classical  composers. Similarly, in 1928, Stravinsky produced The Fairy’s Kiss, a ballet based on Tchaikovsky’s songs and piano pieces. Later, in 1951, Stravinsky’s The Rake’s Progress premiered, a classical style opera which “adopted the eighteenth century convention of recitatives, arias, and ensembles.” (Donald Jay Grout and Claude V. Palisca 1998, p841.) Many view this as the culmination of his neoclassical period.

composers. Similarly, in 1928, Stravinsky produced The Fairy’s Kiss, a ballet based on Tchaikovsky’s songs and piano pieces. Later, in 1951, Stravinsky’s The Rake’s Progress premiered, a classical style opera which “adopted the eighteenth century convention of recitatives, arias, and ensembles.” (Donald Jay Grout and Claude V. Palisca 1998, p841.) Many view this as the culmination of his neoclassical period.

It is important to view these works in their historical context. The start of the twentieth century and end of the romantic era saw the musical landscape dramatically altered. Traditional tonality had completely broken down; chromaticism and dissonance were now common place, and old fashioned chord progressions and harmonic rules were seen as unnecessary and stagnant. Chords and harmonic effects were now exploited for their own intrinsic musical effect, rather than obeying the rigours of modulation and key that had previously governed classical composition. Rhythmic practices had also become more complex, varied and unpredictable. Similarly, musical genres had evolved and mutated into new, ever-changing entities. Symphonies (as with other forms) no longer adhered to set structures. They could be any number of movements long; could last much longer than had previously been common; could often attempt to express increasingly complex emotions, narratives and ideas; and individual movements themselves no longer followed established procedures, often having various different individual identities, and frequently obeying some variety of programmatic subtext rather than adhering to classical music forms. Orchestras themselves had grown to vast proportions, and were made up of various distinct, often obscure instruments, featured together in unusual combinations and sometimes making use of new performance techniques to create further evocative sounds. In combination with this, virtuosity had developed to even greater lengths, as composers demanded more and more from their performers in order to create increasingly striking effects.

Amid all this chaos, many early twentieth century composers sought to re-establish some order, by creating new sets of principles and procedures with which to govern their work. Many composers such as Bartok, Prokofiev or Vaughn Williams took inspiration from their national folk idioms, as indeed did Stravinsky in his early ballets such as The  Firebird, Petrushka and Le sacre du printemps, all of which are “rich in Russian folk songs.” (Donald Jay Grout and Claude V. Palisca 1998, p837.) Another school of composers followed in the footsteps of Arnold Schoenberg and the serialism movement, where a completely new set of rules were established in order to create a new type of music that abandoned tonality, and instead favoured creating moods and effects via inventive use of tone colour and instrumentation.

Firebird, Petrushka and Le sacre du printemps, all of which are “rich in Russian folk songs.” (Donald Jay Grout and Claude V. Palisca 1998, p837.) Another school of composers followed in the footsteps of Arnold Schoenberg and the serialism movement, where a completely new set of rules were established in order to create a new type of music that abandoned tonality, and instead favoured creating moods and effects via inventive use of tone colour and instrumentation.

However, some composers were dissatisfied by this response to the end of romanticism. Instead, they went down a completely different route, whereby rather than abandoning tonality they actually looked back to previous composers from the baroque, classical and romantic periods, and sought inspiration from them in order to bring some clarity to their modern compositional styles. As Palisca and Grout put it, “Composers as never before had a detailed knowledge of many past styles and were aware of the uses they were making of them,” (Donald Jay Grout and Claude V. Palisca 1998, p840) leading them to maintain “familiar features of the past – tonal centres, (defined or alluded to in quite new ways) melodic shape, goal orientated movement of musical ideas, for example – while incorporating fresh and unfamiliar elements.” (Donald Jay Grout and Claude V. Palisca 1998, p826.) This was what became known as ‘neo-classicism.’ Many view Prokofiev’s Symphony No. 1 of 1917 as the first  neo-classical work, based as it was around the traditions of classical symphonies. Stravinsky’s first neo-classical work was 1919’s Pulcinella, based around classical themes recommended to him by Serge Diaghilev. Stravinsky later described the piece as “my discovery of the past, the epiphany through which the whole of my late work became possible.” (Igor Stravinsky and Robert Craft 1962, p113)

neo-classical work, based as it was around the traditions of classical symphonies. Stravinsky’s first neo-classical work was 1919’s Pulcinella, based around classical themes recommended to him by Serge Diaghilev. Stravinsky later described the piece as “my discovery of the past, the epiphany through which the whole of my late work became possible.” (Igor Stravinsky and Robert Craft 1962, p113)

It is very important to establish however, that although Stravinsky and other neoclassical composers were taking inspiration from the past, this was purely as a means of developing their own compositional styles. It wasn’t simply a case of copying and repeating classical composers’ works in the 20th century, but of taking stylistic elements, melodies and ideas from classical composition and ‘re-composing’ them into new pieces of music. This is evident in Stravinsky’s works, where he originates the majority of the music himself, often including a variety of modern techniques and idiosyncrasies but within a noticeably classical framework. As Joseph Strauss puts it, “Traditional elements are incorporated and reinterpreted, but not effaced. Rather, the past remains a living, forceful presence.” (Strauss 1990, 184-85)

An important aspect of this process of ‘re-composition’ is that Stravinsky mainly based his neoclassical pieces on various non-linked pieces written for a singular instrument, or a small combination of instruments. Stravinsky assembled such pieces and then built them into one cohesive work comprised of his own more expansive orchestrations of the original material. Pulcinella for example was based on a variety of different sorts of works for solo instrument or ensembles of up to four players, including trio sonatas, songs and harpsichord pieces. Stravinsky assembled these pieces into a coherent ballet, orchestrating the original works for a small classical orchestra of two flutes, oboes, bassoons, and horns; strings divided into a concertino section and ripieno section; and also a trumpet and trombone. The unlikely inclusion of a trombone is indicative of the type of unusual modern twists Stravinsky added in recomposing these works, and imbues a sense of humor in the piece which is perhaps what Stravinsky had in mind when he spoke of satirizing Pergolesi’s original material: “Who could have treated that material in 1919 without satire?” (Igor Stravinsky and Robert Craft 1962, p113) This gives us an idea of how Stravinsky approached ‘re-composing’; his alterations and additions to the original material mutate the overall identity of the music, and we’re left with an often very different entity to the 18th Century models, brimming with a knowing sense of irony, wit, imitation and affectionate homage.

We see this in other aspects of Pulcinella. There are further unusual orchestrations, such as the oboe and horn combination in the Gavotta, the interplay between double bass and trombone in the Vivo, with numerous comedic glissandi and unusually high double bass writing, and the fact that the double bass is almost completely separate from the cello in a manner most unlike eighteenth century composition. Stravinsky also plays around classical structure in a satirical manner, most notably when he opens the second section of the Vivo in the tonic, as opposed to the dominant as would have been traditional in the eighteenth century. There are also modern rhythmic intricacies, such as adding in extra beats and rests. He includes harmonic features that wouldn’t have been found in the classical era, such as unexpected dissonances and prolonged static chords. The overall effect of all these modifications is to create a multi-layered work that, although classical sounding, clearly has levels of parody and ironic self-awareness.

The Fairy’s Kiss from 1928 is another demonstration of Stravinsky’s ‘re-composition’ of music from an earlier composer. This time he took a  selection of Tchaikovsky’s piano works and songs, and orchestrated them into a ballet. However, in contrast to Pulcinella, there is considerably more of Stravinsky’s own music integrated with the Tchaikovsky material. For the most part, Stravinsky mainly takes small extracts of Tchaikovsky’s melodies and then builds around them with his own ideas, again demonstrating how his neoclassicism was all about ‘re-composing’ earlier music in order to create new works. He develops Tchaikovsky’s original ideas with his own, resulting in a unique hybrid style that works both as homage to Tchaikovsky, but also as a modern take on his romantic style, replete with unexpected moments of Stravinsky’s own compositional character.

selection of Tchaikovsky’s piano works and songs, and orchestrated them into a ballet. However, in contrast to Pulcinella, there is considerably more of Stravinsky’s own music integrated with the Tchaikovsky material. For the most part, Stravinsky mainly takes small extracts of Tchaikovsky’s melodies and then builds around them with his own ideas, again demonstrating how his neoclassicism was all about ‘re-composing’ earlier music in order to create new works. He develops Tchaikovsky’s original ideas with his own, resulting in a unique hybrid style that works both as homage to Tchaikovsky, but also as a modern take on his romantic style, replete with unexpected moments of Stravinsky’s own compositional character.

Similarly, The Rake’s Progress features numerous allusions to and virtual quotations from earlier composers, in particular Mozart, as well as  Monteverdi, Handel, Bach, Gluck and Verdi. As Chandler Carter puts it, the opera “resounds with echoes of distant fanfares and arias, classical textures, florid melismas, and secco recitatives.” (Chandler Carter 1997, p55) It is built up from all the same constituent elements as you would expect from an eighteenth century opera. It also makes use of a classical sized orchestra, and is largely tonal throughout. The opera opens in the countryside, and as such, Stravinsky invokes a pastoral topic, another feature from classical composition.

Monteverdi, Handel, Bach, Gluck and Verdi. As Chandler Carter puts it, the opera “resounds with echoes of distant fanfares and arias, classical textures, florid melismas, and secco recitatives.” (Chandler Carter 1997, p55) It is built up from all the same constituent elements as you would expect from an eighteenth century opera. It also makes use of a classical sized orchestra, and is largely tonal throughout. The opera opens in the countryside, and as such, Stravinsky invokes a pastoral topic, another feature from classical composition.

However, once again Stravinsky is ‘re-composing’ these elements, in order to successfully communicate W.H. Auden’s libretto, which has been described by Geoffrey Chew as “one of the most complex and ‘literary’ of the whole repertory.” (Geoffrey Chew 1993, p239) The most striking aspect of this setting is how Stravinsky makes reference to such a vast range of different composers, with the Monteverdi-like overture, the baroque style ritornellos, and classical arias replete with “Mozart-like turns and appoggiaturas.” (Donald Jay Grout and Claude V. Palisca 1998, p841.) The combination of all these different styles into one work adapted with Stravinsky’s typical stylistic modifications produced a unique piece of music, brimming with a multitude of layers. Different  composers are used to invoke different moments of the story, and there is also a degree of wit and satire once again to take into consideration. This perfectly complements Auden’s multi-layered libretto, itself a period piece that both pays homage to and satirizes its sources. As Stephen Walsh put it, “By combining all these different traditions in one opera, Auden and Stravinsky were not so much re-creating classical opera in a modern image as using a variety of historically connected ideas as co-ordinates for plotting an essentially modern line of thought.” (Stephen Walsh quoted by Jonathan Cross 1998, p13)

composers are used to invoke different moments of the story, and there is also a degree of wit and satire once again to take into consideration. This perfectly complements Auden’s multi-layered libretto, itself a period piece that both pays homage to and satirizes its sources. As Stephen Walsh put it, “By combining all these different traditions in one opera, Auden and Stravinsky were not so much re-creating classical opera in a modern image as using a variety of historically connected ideas as co-ordinates for plotting an essentially modern line of thought.” (Stephen Walsh quoted by Jonathan Cross 1998, p13)

Stravinsky’s neoclassical pieces were highly influential at the time and still are today. During a period when radicalism and experimentation in art were the be all and end all, Stravinsky’s neoclassicism demonstrated the value and continued relevance of the art of the past. It also demonstrated how elements of earlier composition can be successfully utilized in order to create new, multi-layered pieces of work. As Jonathan Cross puts it, “by placing familiar objects in new contexts, he enables us to see them in new ways.” (Jonathan Cross 1998, p13) This influence of Stravinsky’s neoclassicism was soon apparent among his contemporaries, and as Joseph Strauss clarifies, “We are becoming increasingly aware of the common structures that underlie the obvious stylistic diversity of Schoenberg, Webern, Berg, Stravinsky, and Bartok.” (Strauss 1990, p3) And there is no doubt that composers today have been influenced by Stravinsky’s neoclassical approach. Many modern day composers seek influence from all different periods of the past, combining elements from completely contrasting styles with their own postmodern compositional sensibilities, as Stravinsky originally demonstrated was possible. This can be seen with the modern day use of archaic forms such as the suite, the passacaglia, or plainchant; the revival and exploration of older instruments such as the harpsichord, the viol or lute, with new styles and techniques; the revived interest in tonality, and also the frequent composition for smaller, more classically sized orchestras and ensembles. Compositional features such as these are constantly used in new and inventive ways to create groundbreaking modern works.

References

Chandler Carter, (1997) “Stravinsky’s “Special Sense”: The Rhetorical Use of Tonality in “The Rake’s Progress” Music Theory Spectrum 19, p55-80

Geoffrey Chew, (1993) “Pastoral and neoclassicism: A reinterpretation of Auden’s and Stravinsky’s Rake’s Progress” Cambridge Opera Journal 5, 3, 239-263

Jonathan Cross, (1998) The Stravinsky Legacy, CUP

Donald Jay Grout and Claude V. Palisca, (1998) A History of Western Music: Fourth Edition, J. M. Dent and Sons Ltd

Joseph Straus, (1990) Remaking the Past, Harvard University Press

Igor Stravinsky and Robert Craft, (1962) Expositions and Developments, Faber

Related articles

- How someone got arrested for making the world a better place.. (skyscraperyoga.wordpress.com)

- Stravinsky’s “Fanfare for a New Theatre,” played by Friedrich & Bauer (talkingtrumpet.wordpress.com)

- Can classical music be considered Christian (wiki.answers.com)

- Stravinsky, other Moderns at symphony (seattletimes.nwsource.com)

- Classical Music: As summer turns to fall, You Must Hear This 2: Francis Poulenc’s Concerto for Two Pianos (welltempered.wordpress.com)

[…] Old Ground, Fresh Territory: Re-Composition in the Neoclassical Ballets and Operas of Stravinsky (higherrevelations.wordpress.com) […]