In order to understand Mahler’s approach to orchestration, it is necessary to establish the context of the era in which he was composing. At this point, music had evolved to extreme proportions. Pieces were longer, more ambitious, more programmatic, and called on greater resources than ever before. The end of the romantic era saw composers increasingly looking for new and varied ways to further develop their art and match the enormous artistic achievements of past composers, notably Bach, Mozart and Beethoven. Harmony had developed beyond its traditional role and functions, and it would not be long before it was abandoned altogether. Composers were also more experimental in the sorts of works they were writing; programme music was common, the genre of symphonic or tone poems had developed, and traditional symphonies themselves were subject to tremendous expansion and experimentation.

In keeping with this experimentation was the approach to orchestration during this period. Composers were seeking new and exciting ways of orchestrating their music, in order to fully satisfy their loftier artistic inclinations and ambitions, and to fit the exotic new harmonies that were now being explored. No composer more than Mahler sought to develop the art of orchestration, and in doing so he would present a whole variety of challenges to orchestras of the time. Players would frequently have to learn new concepts and techniques in order to successfully perform his works. It has been said of Mahler as a composer that he “came to conceive that a symphony might give voice to ‘the whole of nature,’” (P. Franklin, 1996, xii) and so it is perhaps not surprising that he would then seek to explore the orchestra to its utmost expressive potential.

In keeping with this experimentation was the approach to orchestration during this period. Composers were seeking new and exciting ways of orchestrating their music, in order to fully satisfy their loftier artistic inclinations and ambitions, and to fit the exotic new harmonies that were now being explored. No composer more than Mahler sought to develop the art of orchestration, and in doing so he would present a whole variety of challenges to orchestras of the time. Players would frequently have to learn new concepts and techniques in order to successfully perform his works. It has been said of Mahler as a composer that he “came to conceive that a symphony might give voice to ‘the whole of nature,’” (P. Franklin, 1996, xii) and so it is perhaps not surprising that he would then seek to explore the orchestra to its utmost expressive potential.

The most obvious way in which Mahler presented a challenge to his orchestras was the sheer size of orchestra he frequently insisted upon. From his earliest symphonies onwards, he expanded the amount of instruments he used to proportions that no previous composers had written for.

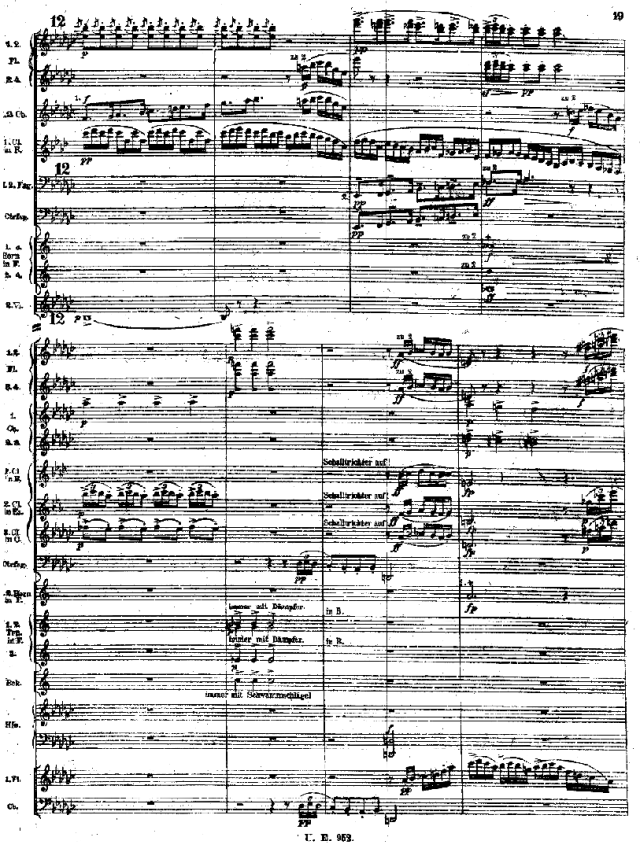

In one of his earliest works, Das Klagende Leid, he begins his development of the use of the orchestra. “Even in the original version the handling of the orchestra- an exuberantly large one for the time- shows unusual flair and imagination for a young composer.” (D. Mitchell, 1980, p511) This would further develop throughout each of the symphonies. As Donald Grout and C.V Palisca put it, “Mahler’s symphonies are typical post- romantic works: long, formally complex, programmatic in nature and demanding enormous performance resources. Thus, the second symphony, first performed in 1895, requires, along with a huge string section, 4 flutes (two interchangeable with piccolos) 4 oboes, 5 clarinets, 3 bassoons and a contrabassoon, 6 horns and 6 trumpets (plus 4 more of each, with percussion in a separate group) 4 trombones, tuba, kettledrums and numerous other percussion instruments, 3 bells, 4 or more harps and organ, in addition to soprano and alto soloists and a chorus.” (D. J. Grout and C. V. Palisca, 1988, p758)

Needless to say, this is a vast orchestra, much larger than most of the instrumentalists would have been used to playing in, and the amount of rehearsal that would have been required in order to successfully combine all these forces into a cohesive, expressively effective unit would have been much greater than was common at the time. However, Mahler felt such forces were necessary in order to achieve the grand programmatic scheme of this 5 movement masterpiece, an emotional journey that moves from contemplating death to celebrating life. This use of such vast orchestration would culminate in the renowned eighth symphony, the ‘Symphony of a Thousand’ so-called because of the vast forces it requires, in order to achieve Mahler’s positive affirmation of the glory of the human spirit. As Henry-Louis de-la Grange put it, “”To give expression to his cosmic vision, it was … necessary to go beyond all previously-known limits and dimensions.” (H.D.L Grange, 2000, p890)

One aspect of all of these works in addition to the large instrumental forces being deployed is the inclusion of vocal soloists and choruses in the orchestra. Mahler was always a composer to take inspiration from his background, and his history composing Lied would have a deep impact on his symphonies. Often he would choose texts that further added to the programmatic depth of what he was trying to achieve. As Grout and Palisca put it, “Mahler the symphonist cannot be separated from Mahler the song composer.” (D. J. Grout and C. V. Palisca, 1988, p760) He was one of the first composers since Beethoven and his ninth symphony to use voices within a symphonic context.  He was best known as an operatic conductor, and so inevitably would have had more experience at marrying vocal and instrumental forces. Indeed, it has been argued by Donald Mitchell that “Mahler was influenced by the large scale thinking in Wagnerian music drama.”(D. Mitchell, 1980, p514) His first four symphonies would all include vocal forces, most notably in the second, where, “like Beethoven, Mahler brings in voices for the final climax of the work…The third movement is a symphonic adaptation of one of the Wunderhorn songs, and the brief fourth movement is a new setting for contralto solo of still another poem from that collection. This serves to introduce the finale…a monumental setting for soloists and chorus beginning with the text of a Resurrection ode.” (D. J. Grout and C. V. Palisca, 1988, p758) In this symphony, you clearly see the influence of his past, and also of the music of Beethoven and Wagner; most notably, the aim to produce such a monumental and ambitious work, by making use of such extensive forces and achieving a balance between orchestra and voice.

He was best known as an operatic conductor, and so inevitably would have had more experience at marrying vocal and instrumental forces. Indeed, it has been argued by Donald Mitchell that “Mahler was influenced by the large scale thinking in Wagnerian music drama.”(D. Mitchell, 1980, p514) His first four symphonies would all include vocal forces, most notably in the second, where, “like Beethoven, Mahler brings in voices for the final climax of the work…The third movement is a symphonic adaptation of one of the Wunderhorn songs, and the brief fourth movement is a new setting for contralto solo of still another poem from that collection. This serves to introduce the finale…a monumental setting for soloists and chorus beginning with the text of a Resurrection ode.” (D. J. Grout and C. V. Palisca, 1988, p758) In this symphony, you clearly see the influence of his past, and also of the music of Beethoven and Wagner; most notably, the aim to produce such a monumental and ambitious work, by making use of such extensive forces and achieving a balance between orchestra and voice.

Mahler didn’t just expand the orchestra as a whole. He also paid particular attention to increasing the role of specific portions of the orchestra. Notably, he avoided over-relying on thick string textures as had become a cliché of some romantic music, most notably in the symphonies of Schumann, where the string writing has often been criticised as having far too prominent a role. This has also been claimed to a lesser extent of Brahms, who it could be argued was never quite as imaginative in terms of his writing for brass and woodwind as he was for strings. Mahler sought to redress this balance, finding wind and brass textures incredibly useful for the sort of sounds he wanted to create. This was often in order to create dark and brooding timbres, as are frequently found in the second symphony, particularly in the “vulgar, rowdy brass band Resurrection march.” (D. Mitchell, 1980, p516) Mahler also frequently invoked music of a military nature, such as in the third symphony. “Mahler makes good use of the very large orchestra the third symphony demands. Above all of the big battalions of wind: quadruple woodwind (but 5 clarinets, two of which are E flat clarinets, commonly found in military bands) 8 horns, 4 trumpets, 4 trombones and tuba. With these resources to hand he is able to bring to his busy motivic textures the maximum of clarifying instrumental colour.” (D. Mitchell, 1995, p327)

This would have undoubtedly been a challenge for orchestras of the time, most obviously players in the brass and woodwind sections who suddenly had a lot more to do than they had been given in the music of other composers. Now, not only were they not in a secondary role to the strings, they were actually often more prominent. “Again and again in the fourth symphony we find pages of scoring where the wind predominate; and indeed the general impression left by the symphony is one of a sound world to which the wind make the major contribution…in this work he has effected a radical shift away from the classical concept of the predominantly string-based orchestra.” (D. Mitchell, 1995, p325) Many would argue that Mahler was the first composer to have done this since Beethoven, whose first symphony was famously criticised for having too predominant wind textures.

Mahler was also not afraid of being highly experimental with his choice of instrumental combinations and effects. “Mahler’s orchestration continued the innovations introduced by Berlioz. His flair for finding unusual and effective combinations of instruments is always distinctive.” (Anonymous, The Symphony: An Interactive Guide – Late Romanticism, http://library.thinkquest.org/ 22673/mahler.html) Many of these more experimental moments were designed to achieve the sort of unusual expressive effects required by the programmatic content of his music. For example, he would frequently employ off-stage ensembles, an effect he utilised as early as in Das klagende Lied where he sets “the catastrophe of the final scene of this work against an offstage wind band which pursues its festive music despite the calamitous dramatic context…the association of high tragedy and the mundane (the wind timbre of the offstage band), the latter simultaneously (offers) an ironic commentary on the former.” (D. Mitchell, 1980, p511)

This unusual effect would reoccur in other of Mahler’s works, and was undoubtedly a difficult exploit to achieve due to the obvious problems presented by having performers offstage trying to play in time with performers onstage. It is also indicative of the very specific programmatic evocations Mahler was so talented in arousing.  He was a master at using instruments in unusual ways to imply narrative elements, such as in the Scherzo of the fourth symphony, where “the scordatura solo violin – all strings tuned one full tone higher than normal…is intended to suggest the sound of the medieval Fiedel (fiddle) in a musical representation of the Dance of Death, a favourite subject in old German paintings.” (D. J. Grout and C. V. Palisca, 1988, p758)

He was a master at using instruments in unusual ways to imply narrative elements, such as in the Scherzo of the fourth symphony, where “the scordatura solo violin – all strings tuned one full tone higher than normal…is intended to suggest the sound of the medieval Fiedel (fiddle) in a musical representation of the Dance of Death, a favourite subject in old German paintings.” (D. J. Grout and C. V. Palisca, 1988, p758)

Another challenge for orchestras aside from achieving these effects was to find good players on rare orchestral instruments such as the mandolin. A notable example of this is in the seventh symphony, where “The second Nachtmusic…is Mahler’s equivalent of a Schumann character piece, a kind of extended Albumblatt for a large and idiosyncratic orchestra (mandolin and guitar are prominent.” (D. Mitchell, 1980, p511)

In creating such vivid pieces, an enormous amount of instruction is given in the score, so each effect is achieved to its most optimum potential, including “extremely detailed indications of phrasing, tempo, and dynamics.” (D. J. Grout and C. V. Palisca, 1988, p758) Interestingly, he was often able to recreate the effect of having an offstage ensemble through scoring alone, such as in the Ninth Symphony, and its use of a chamber orchestra. “Extremely subtle dynamic markings and through orchestration…allow mobility between differently constituted bodies of sound, as with the chamber orchestra which suddenly emerges in the Ninth Symphony’s first movement without leaving the main arena of musical action.” (D. Mitchell, 1980, p517)

In his later works Mahler would present yet another challenge to orchestras in his employment of increasingly contrapuntal textures, a style of writing that was not common during this period.

He was frequently drawn to baroque composers as sources of inspiration, most notably Bach, and this use of counterpoint would prove challenging given the sheer amount of players involved in playing simultaneous, contrasting lines, not to mention the length of the works also. “This new aspect of Mahler’s technique appears with special force in the finale of the sixth, which sustains page after page of counterpoint, almost Palestrinian in its breadth.” (D. Mitchell, 1980, p523)

All in all, Mahler’s music was renowned at the time and still is today for the complexity of its orchestration. The sheer scale, the use of voice, the development of the orchestra, the experimentation, the level of detail, and the complicated textures all combined to produce music that was as demanding for orchestras to play as it was rewarding for audiences to hear. The breadth of orchestral writing employed was vital in achieving the ambitious artistic aims of his works; most notably, the detailed and profound programmes he wished to evoke.

Bibliography

Anonymous, The Symphony: An Interactive Guide – Late Romanticism, http://library.thinkquest.org/ 22673/mahler.html

H. D. L. Grange, Gustav Mahler Volume 3: Vienna: Triumph and Disillusion (1904–1907), (Oxford University Press, 2000)

D. J. Grout and C. V. Palisca, A History of Western Music, (J. M. Dent and Sons Ltd, London, 1988)

P. Franklin, Mahler: Symphony No. 3, (Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge, 1996)

D. Mitchell, Gustav Mahler: Volume 2 – The Wunderhorn Years, (University of California Press, 1995)

D. Mitchell, The Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians: Mahler, (Oxford Univeristy Press, 1980)

Related articles

- Gustavo Dudamel’s Mahler project (latimes.com)

- Classical music: Taking the measure of Mahler in Japan. (welltempered.wordpress.com)

- How Charlotte Church Ruined Gabriel Fauré’s Pavane Op. 50 (higherrevelations.wordpress.com)

- The Year in Mahler (thebigcityblog.com)

- Old Ground, Fresh Territory: Re-Composition in the Neoclassical Ballets and Operas of Stravinsky (higherrevelations.wordpress.com)

- Bluejay: The reincarnation of Gustav Mahler? (personalityspirituality.net)

- Rachmaninov, Liszt and Mahler coming up at symphony (seattletimes.nwsource.com)

- Gustav Mahler – By Jens Malte Fischer – Book Review (nytimes.com)

- Mahler: Symphony No 6 – review (guardian.co.uk)

- Moto Perpetuo Mahler (lietofinelondon.wordpress.com)

[…] The miscellany of the intertubes … my post on Mahler brought up a ping-back that led me to this good article on Mahler’s orchestration … quite often, the web is like high school, full of people […]